About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

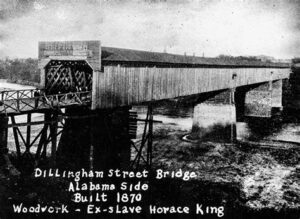

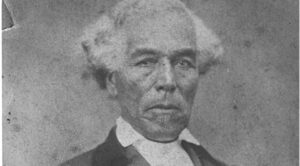

Born as a slave of African, European, and Native American (Catawba) ancestry in Chesterfield District, South Carolina, King moved with his master, John Godwin (1798-1859), a contractor, to Girard, Alabama, a suburb of Columbus, where Godwin had the contract to build the first public bridge connecting those two states. King probably planned the construction and directed the slaves who erected that span. Godwin apparently realized King’s intuitive genius as a builder and nurtured those skills. During the early 1840s, King served as superintendent and architect of major bridges at Wetumpka, Alabama, and Columbus, Mississippi, without Godwin’s supervision.

In the mid-1850s King built Moore’s Bridge, over the Chattahoochee River between Newnan and Carrollton, and accepted stock in the enterprise as payment. King’s wife, Frances Gould Thomas (1825-64), a free black woman whom he married in 1839, and their five children are believed to have moved to this site, perhaps by 1858. There they tended the bridge and farmed until 1864 when the Union cavalry burned the span. During this period King moved freely about the South, apparently maintaining a home at Moore’s Bridge and one in Girard.

The Civil War (1861-65) brought an economic boom to Columbus, and King, like other local contractors, worked for the Confederacy. He supplied timbers and erected a major building for the Confederate navy there. The Alabama governor pressed King into service, against his will, to place defensive obstructions in the lower Alabama River. King claimed that the federal government owed him, as a Unionist, for the confiscation or plundering of his property by Union troops. Immediately after the war ended in 1865, a year after the death of his first wife, he married Sarah Jane Jones McManus, with whom he had no children.

King’s children—Washington W. (1843-1910), Marshall Ney (1844-79), John Thomas (1846-1926), Annie Elizabeth (1848-1919), and George (1850-99)—continued the work of the King Brothers Bridge Company. They built bridges and various structures in LaGrange, Atlanta, and east Alabama. John T. King served as a trustee for Clark College (later Clark Atlanta University) from the 1890s until the 1920s and was one of the contractors who built the Negro Building at the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition in 1895.

For more than a century the achievements of King have been well known in the Lower Chattahoochee River Valley. Local writers and chambers of commerce proudly proclaim their Horace King bridges or buildings even when there is little or no real historical evidence to verify many of the claims. King’s legendary status stems from three factors: he was an excellent bridge builder, the best in the region; he forged a career that was unique for a man of color; and his exp

For more than a century the achievements of King have been well known in the Lower Chattahoochee River Valley. Local writers and chambers of commerce proudly proclaim their Horace King bridges or buildings even when there is little or no real historical evidence to verify many of the claims. King’s legendary status stems from three factors: he was an excellent bridge builder, the best in the region; he forged a career that was unique for a man of color; and his exp erience appeared to embody slavery at its best, a kinder and gentler form of servitude. Slavery must not really be that bad, local historians implied if this slave erected a monument to his master. In this way, King unwittingly became an apologist for slavery. In recent years he has been cited as a black Confederate, an African American who supported the Southern cause. If his Unionist testimony reflected his true opinion, however, King shunned any association with the Confederacy.

erience appeared to embody slavery at its best, a kinder and gentler form of servitude. Slavery must not really be that bad, local historians implied if this slave erected a monument to his master. In this way, King unwittingly became an apologist for slavery. In recent years he has been cited as a black Confederate, an African American who supported the Southern cause. If his Unionist testimony reflected his true opinion, however, King shunned any association with the Confederacy.Lupold, J. S., & French, T. L. (n.d.). Horace King (1807-1885). Retrieved February 14, 2021, from https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/horace-king-1807-1885