About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

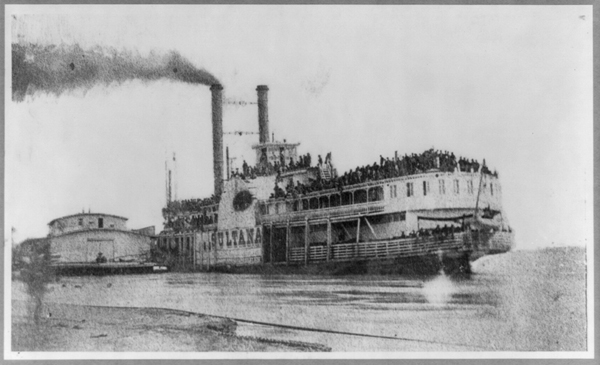

The worst maritime disaster in American history occurred on April 27, 1865, when the steamship Sultana exploded and burned on the Mississippi River while dangerously overloaded with passengers. The Sultana, a typical side-wheeler coal-burning steamer, was built in 1863. It made frequent trips up and down the Mississippi River between New Orleans and St. Louis during the war, often carrying military personnel. After a regular run from St. Louis, the Sultana left New Orleans on April 21 carrying about 100 passengers, assorted goods, and livestock. The ship’s engineer discovered leaks in the boilers during a regular stop at Vicksburg on April 24 and hasty repairs were made. Following the repairs, the Sultana proceeded to board 1,800 to 2,000 passengers, all repatriated Union prisoners desperate to get home from prison camps at Cahaba in Alabama and Andersonville in southwest Georgia.

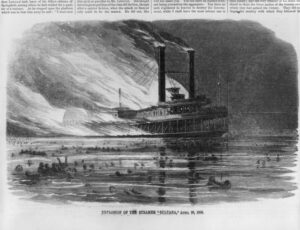

The ship stopped in Memphis for more repairs to the boiler, then, at about 1:00 a.m. on April 27, the Sultana, now dangerously overloaded, proceeded up-river toward Cairo, Illinois. About seven miles north of Memphis the boilers suddenly burst. The violent and tremendous explosion tore the center out of the vessel, instantly scalding and burning some of the passengers with steam and fire. The blast threw many passengers into the water; however, many remained trapped aboard the ship, where they either perished or were maimed by the heat of the explosion and the collapsing ship. To escape the burning steamer, some passengers leaped into the river, where they faced hours in the dark, frigid water listening to the shrieks and cries of the injured and dying. The exact death toll remains unknown. Though the official number of deaths is recorded as 1,547, modern historians believe the number could be as high as 1,800, making the Sultana disaster even more terrible than the better-known Titanic tragedy: slightly more than 1,500 passengers were lost when the much-larger ocean liner sank in the North Atlantic 47 years later.

Many Sultana survivors ended up on the Arkansas side of the river, which was under Confederate control during the war. And many of them were saved by local residents, like John Fogelman — an ancestor of the city of Marion’s current mayor, Frank Fogelman. Newspaper accounts suggest John Fogelman and his sons spotted the burning Sultana as the remains of the paddle-wheeler drifted downriver. “The wind blew the fire to the rear, burned that out,” Frank Fogelman says. “The paddle wheel fell off of one side, caused the boat to turn sideways; the other paddle wheel fell off.” Eventually, the Sultana turned so that the wind was pushing the flames toward the bow, where 25 soldiers remained. Fogelman’s ancestors didn’t have any boats to reach the trapped soldiers, so they improvised. “I understand that the Fogelmans were able to put together some logs to make a raft and go out and take people off the boat as it drifted back this way,” Fogelman says. “In order to save time, they would set the people off in treetops, and go back to the boat to take more off.” All 25 soldiers were rescued, historians say, and the Fogelman home became a refuge for Sultana survivors. Passing boats and bystanders on both sides of the Mississippi helped pull survivors from the muddy water. But some of the most poignant stories involve Confederate soldiers rescuing their Union counterparts. Frank Barton is the descendant of one of those Confederate soldiers, a man named Franklin Hardin Barton. “He served in the 23rd Arkansas Cavalry, and he was tasked with, among other things, raiding ships going up and down the river,” Frank Barton says. “A few weeks earlier, he might have been attacking the Sultana if it had come in.” Instead, newspaper accounts say Franklin Barton saved several Union soldiers.

Sultana Aftermath, 1865

Within hours of the disaster, Gen. C. C. Washburn, commanding officer at Memphis, appointed a military commission to investigate the tragedy. Three inquiries followed to investigate post-war suspicions that a Confederate bomb had been aboard and reviewing the state of poorly repaired boilers and the impact that overcrowding had in the disaster. The official cause of the explosion was determined to be mismanagement of water levels in the boilers, the ship’s listing back and forth in the water due to severe overcrowding, and the faulty repairs made to the boilers days before the disaster. Capt. Frederick Speed was the only official found guilty of any impropriety and was court-martialed. However, the findings were later reversed and no one ever faced official charges.

Surprisingly, the Sultana disaster received very little coverage in the contemporary media. This omission was partially due to the public’s having become somewhat desensitized to death toll numbers during the Civil War, but more specifically it was due to the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, who had been shot and killed at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865, only thirteen days before the Sultana explosion. Overshadowed by the death of a so “monumental” individual, the deaths of the hundreds on board the Sultana received hardly a mention.

Years later the survivors of the Sultana petitioned Congress for a pension, but the request was met with indifference. Funds for the survivors, their families, or a memorial for the incident were not allocated. A group of the survivors met for many years every April 27 and ultimately erected a monument at Mount Olive Cemetery near Knoxville, Tennessee; it reads:

“In memory of the men who were on the Sultana that was destroyed, April 27, 1865, by explosion on the Mississippi river near Memphis, Tennessee.”

In the aftermath of the Sultana explosion, Captain Frederick Speed, a federal officer in charge and assistant adjutant general for the Department of the Mississippi, was accused of knowingly overloading the ship seven times over the legal passenger capacity.

After lengthy testimony, a military commission appointed to investigate the tragedy eventually charged Captain Speed with “neglect of duty to the prejudice of good order and military discipline.” Speed was the only individual ever to face charges resulting from the incident and, though a court-martial eventually found him guilty, the decision was later reversed and the Army closed its investigation. Many officials must have been well aware of the condition of the ship and the overcrowding on board, but ultimately no one was ever formally held responsible for the Sultana tragedy.