About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

The passengers were almost evenly divided between religious separatists (who called themselves Saints) and others, not of their faith, whom they called Strangers. They were supposed to have landed in Virginia but had been blown off course, and upon realizing they were some 500 miles north of where they should be and that the authority granted to them by the Virginia Company who had issued their legal charter was void in this region, some of the Strangers noted that English law did not apply here and claimed that, once ashore, they would live as they pleased and it would be every man for himself.

Members of the separatist congregation, however, as well as – it seems – a number of the Strangers realized they would not survive if they did not all work together for the common good. The compact stipulated that the undersigned agreed to a democratic form of government for the colony where officials would be elected, and laws passed, in the interests of all. Every male member of the colony over 21 years of age would be able to vote for these officials and laws, have the right to change laws or remove those in authority, and propose news laws based on a popular vote; by signing the compact, one agreed to these stipulations, and the majority of those present did so.

The Mayflower Compact would not only provide the Plymouth Colony with its form of government and legislation but would influence later important documents in United States’ history such as state constitutions, the Declaration of Independence, and the U.S. Constitution. It is recognized as one of the most important documents in world history in setting a precedent for the establishment of a democratic government by the consent of the governed.

The Mayflower voyage was conceived by members of the separatist congregation of Leiden, the Netherlands, who had fled religious persecution in England by the Anglican Church under King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE). The separatists were Puritans, Protestant Christian fundamentalists who believed in a literal reading of the Bible, who wanted to see the Church “purified” of any non-biblical aspects such as clergy wearing vestments, the use of incense and music in worship, and adherence to the Book of Common Prayer. The separatists differed significantly from other Puritans, however, since they believed the church was corrupt, could not be saved, and true believers needed to separate themselves from it. Since the king was the head of the Church, any criticism of church doctrine was considered treason, and separatists were arrested, tortured, and executed.

The congregation, under the leadership of their pastor John Robinson (l. 1576-1625 CE), left their homes in Scrooby, England for the Netherlands because of the Dutch policy of religious tolerance, but because they were foreigners in a land where well-paying jobs were controlled by guilds that favored nationals, they could only find menial work as laborers. They accepted this and other hardships in order to practice their faith while trying to raise money to travel elsewhere until 1618 CE when one of their leading members, William Brewster (l. 1568-1644 CE) published a tract critical of the Church and English officials were sent to arrest him. Brewster was protected by the congregation, but they understood that the time had come for them to leave.

Two of the congregation’s members, John Carver (l. 1584-1621 CE) and Robert Cushman (l. 1577-1625 CE) negotiated with the merchant adventurer Thomas Weston (l. 1584 – c. 1647 CE), a man who matched prospective colonists with financial backers, to assist them in establishing a colony in North America in the region of the Virginia Patent, granted by King James I to the Virginia Company of London in 1606 CE. The Virginia Company had successfully founded Jamestown in 1607 CE, a thriving settlement by 1618 CE, and Weston was able to get them a charter for a colony in the same region.

Weston was not interested in the separatists’ religious beliefs or problems with the Anglican Church; his concern was entirely with making money for himself and the investors. To that end, he hired some and invited others to join the expedition whose skills, he felt, would prove useful in establishing the colony. These were the people the separatists called Strangers. Among them were Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE), hired as military advisor, and Stephen Hopkins (l. 1581-1644 CE), the only passenger who had experience in the Americas having been shipwrecked off Bermuda and worked at Jamestown.

Carver and Cushman, often at odds with each other and Weston, managed to outfit the expedition by July 1620 CE. A friend or member of the congregation procured them a passenger ship, the Speedwell, and Weston rented the party a cargo carrack, the Mayflower, for the journey. The Mayflower’s captain was Christopher Jones (l. c. 1570-1622 CE), and the Speedwell was captained by one Mr. Reynolds (dates unknown). The passengers were divided between the two ships, along with their personal belongings.

The Mayflower was 12 years old in 1620 CE, but the Speedwell was a much older ship which had taken part in the 1588 CE battle against the Spanish Armada and was in poor condition. After the two ships left for North America, the Speedwell began taking on water, and the expedition had to return to land twice for repairs. After the second time, they understood the ship would never survive a transatlantic crossing, and it was abandoned. Some of the passengers remained behind while others boarded the already cramped Mayflower.

The Mayflower was never intended to carry a large number of people – it was a cargo ship – and so the 102 passengers who finally set sail were quartered in the ‘tween deck (the gun deck between the main and cargo hold) where there was little light and constant draft and damp. At least two dogs were also on board as well as chickens, goats, and other animals. The separatists were disappointed at having to travel with the Strangers as they had thought they would be making the trip as a cohesive group, and the Strangers, it seems, were no more pleased with the separatists’ rigid religious beliefs and practices.

The delays caused by the Speedwell meant that the Mayflower did not set off until 6 September 1620 CE, and the trip across the Atlantic was much rougher than it would have been, had they left in July. The first half of the voyage, according to the account of separatist William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE), was smooth sailing with a strong wind, but that soon changed as huge waves crashed against the ship and the passengers were almost continuously soaked by seawater coming through the portholes and from the wash across the main deck above them. Whatever tensions there may have been between separatists and Strangers could not have been improved by these conditions.

When, after two months, they came in sight of land – on 9 November 1620 CE – they must have welcomed it, but Captain Jones quickly realized that, wherever they were, they were not where they were supposed to be. The region of modern-day Massachusetts was known to Jones, his crew, and the passengers. It had been mapped by Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE), of Jamestown fame, in 1614 CE, and the separatists had purchased some of these maps in preparation for their trip. Once Jones realized where they were, he attempted to head south to their destination, but bad weather and dangerous shoals forced him to turn back toward where they had first sighted land off Cape Cod.

The problem was that the Mayflower had no legal right to land there nor had the passengers any authority to found a colony in that region. James I had granted charters to the Virginia Company of London and the Plymouth Company with the understanding that each would establish colonies away from the other so as not to infringe on the other’s prospects. The passengers had been granted a charter to found a colony only in the specified region settled by the Virginia Company of London. The land they found themselves before in November 1620 CE was under the jurisdiction of the Plymouth Company and so their charter was invalid and the laws they expected to find already established were non-existent.

A number of the Strangers (no names are given in Bradford’s account) pointed out that the charter they had been given no longer applied as it was only valid in the Virginia Patent. Therefore, in Bradford’s words, they said that “when they came ashore, they would use their own liberty, for none had power to command them” (49). They claimed it would now be every man for himself, and this was clear, they maintained, because none among them had any legal right to govern any other.

Scholar Jonathan Mack suggests three possibilities for the source of the Strangers’ dispute:

Mack notes how the separatists were a tightly-knit community of believers who had lived together in Leiden and whose religious beliefs were far more rigid than those of the Strangers. The Strangers would have been members of the Anglican Church and would have objected to being governed by Puritans. At the same time, none of the Strangers had known each other until they boarded the ship and so had no reason to care what happened to each other.

Christopher Martin (l. c. 1582 – winter of 1620/1621 CE) was hired by Weston, Carver, and Cushman to purchase supplies for the expedition but was accused by the separatists of mismanagement of funds as the supplies never appeared and he seems to have kept their money. Further, in his role as ship’s governor, he is noted by Bradford and another prominent separatist Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655 CE) as arrogant and abusive to the passengers. The Strangers, therefore, may have feared that Martin would now continue as governor of the colony.

The third possibility Mack suggests is that those who raised the objections knew of Stephen Hopkins’ experience in the same situation. In 1609 CE, Hopkins had been aboard the Sea Venture on a supply mission from England to Jamestown when the ship was wrecked off the coast of Bermuda. The leaders of that expedition, Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622 CE) and Sir George Somers (l. c. 1544-1610 CE), maintained they still had authority over the others, but Hopkins objected because they were not under English law and so each man was free to do as he pleased. Hopkins was arrested, ordered to be executed for treason, and was only saved by contrition and pleas for his life.

It is unlikely, as Mack notes, that Hopkins would have instigated the same sort of trouble aboard the Mayflower as he had in Bermuda as this time he was traveling with his family and servants and had a substantial stake in making the colony a success. The first possibility regarding distrust of the separatists and a lack of cohesion among the Strangers is more likely, but the most probable is the objection to Martin continuing on as governor of the colony. When the Sea Venture was wrecked on Bermuda, Gates and Somers were able to assert authority as members of the upper class, but Martin was not the social superior of anyone on board and, by all accounts, was haughty, rude, and untrustworthy.

It is unknown who, specifically, proposed the Mayflower Compact – though likely candidates are John Carver, William Bradford, Edward Winslow, and Stephen Hopkins – or a combination of the four or more. Bradford only gives the subject a single line:

It was believed by the leading men among the settlers that such a deed [the Compact], drawn up by themselves, considering their present condition, would be as effective as any patent and, in some respects, more so. (49)

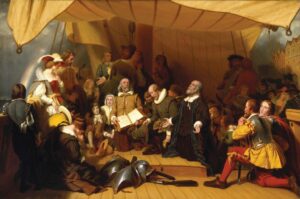

Carver most likely drafted the compact which was read aloud and then signed by 41 of the male passengers. Those who chose not to sign were servants who, though over the age of 21, owing to their status, would have to obey their masters anyway. The compact reads:

IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honor of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience.

IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620.

The compact was carefully worded so it would be clear that none of the colonists were claiming the authority to establish law – as that was the sole right of the king – and so, even though the separatists had many grievances against James I, he is noted as their sovereign and they as his loyal subjects in the first line and referenced again in the last. The purpose of the compact is also made clear in that it is being written in order to ensure the establishment and preservation of a colony to be founded for the “advancement of the Christian faith and the honor of our king and country” and not in the personal interests of any of the undersigned.

The compact thereby protected the signers from any charge of treason in trying to establish their own government over an independent settlement while also assuring those among them, who had objected to the rule of law, that they had a voice and a vote in any decisions concerning the new colony. In signing, all agreed to abide by the compact and, shortly afterwards, Carver was elected as their governor. Once the compact had been ratified, Carver ordered the expedition to continue, and the Mayflower dropped anchor.

The compact is the first known European agreement by which a government was established by the will and through the consent of those governed. Earlier documents, such as the Magna Carta, were forced on a monarch by the nobility, but the Mayflower Compact was drafted and signed by commoners, all of about equal social status, in the recognition that working together for the common good was more beneficial than insisting on pursuing one’s own to the detriment of others. This equalitarian aspect of the compact would later influence the philosophy and vision of the founders of the United States.

The Mayflower Compact is thought to have been modeled on the covenant of the Leiden congregation, written by John Robinson, in which all who signed agreed to a single vision of faith and recognition of a common goal. The phrasing of the compact and Robinson’s covenant are quite similar. The compact allowed for Carver, as governor, to assign responsibilities to members of the party with the clear expectation that they would be carried out. Scouting missions were launched, shelters built, and the sick cared for in accordance with the needs of all, not of the few.

After the colony was established at Plymouth, and the Native Americans of the Wampanoag Confederacy had initiated friendly relations, the compact served as the model for the peace treaty between the colonists and the Wampanoag chief Ousamequin (better known by his title Massasoit, l. c. 1581-1661 CE) which would maintain a close and mutually beneficial relationship between the newcomers and Native Americans until Massasoit’s death and the influx of more colonists of the Massachusetts Bay Colony who required more and more of the natives’ land.

The Mayflower Compact’s significance would continue, however, long after the Plymouth Colony itself had been absorbed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691 CE as the inspiration for the early constitutions of states such as Massachusetts and Connecticut. It would inspire the thinkers now known as the Founding Fathers to question the legitimacy of England’s control over the original 13 colonies of North America, leading to the American Revolution (1775-1783 CE) and its ideals are echoed in the Declaration of Independence of 1776 CE. Later, after the colonies had gained their independence from England, the Mayflower Compact would inform the drafting of the United States Constitution and so still exerts the same influence in the modern era as it did 400 years ago when people of different faiths and backgrounds agreed to work together toward a vision grander than each could achieve separately.