About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

On March 26, 1857, William Ellison wrote to his son Henry Ellison about the family business. Life was going well and Ellison wanted to update his son on how things were going at home. John, one of Ellison’s 53 slaves had just been to the river to collect payment from a number of white slaveowners for the cotton gins they had purchased from Mr. Ellison. He came back with no money at the end of the day though. Ellison’s customers had either made excuses such as wanting to consult their overseer before paying or had not been where they said they would be. There was no frustration in Ellison’s tone as though this is something that he has had to deal with before. He then gave instructions to his son to purchase a number of farming tools that would inevitably be used in the fields by his slaves. He gave a brief farewell and ended the letter.

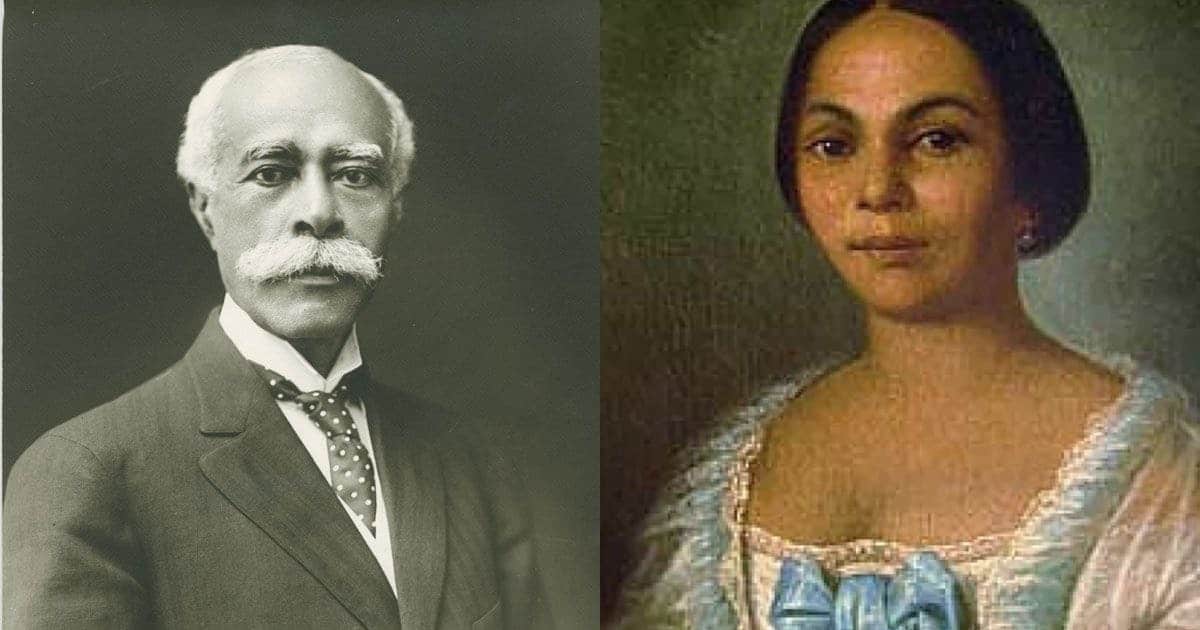

This same type of letter may have been sent a thousand times from a slaveholding father to his slaveholding son in mid nineteenth century American South. But William Ellison and his son, Henry Ellison, were different. William Ellison was African American, born into slavery in April of 1790 with the name April Ellison to a slave mother and white slavemaster father, Mr. William Ellison. As a young man he was apprenticed to a cotton gin maker rather than working in the fields and allowed to keep a portion of the wages he earned for his master and father, money that he later used to purchase his freedom.

At the same time, he changed his name to William Ellison, after his father, to fit in with higher society. After purchasing his family, he moved to Sumter County, South Carolina and hired out other free African Americans to work in his cotton gin shop. While working, he discovered a common problem among freed slaves in the South. The expense of wages left him with a profit that would never compete with what slaveowners were earning. Wanting to move up in society, he purchased his first slaves in 1820.

By 1850, Ellison had 37 slaves while his sons owned another 16. He was one of about 180 black slave masters in South Carolina at the time, most of whom were former slaves themselves. Like Ellison, they realized that the only way to get out of the lower middle class that so many freed blacks were stuck in, was slave labor. With nearly 9,000 free blacks in South Carolina, that 180 made up a tiny percentage who were willing to do anything to compete with the upper class white slaveowners at the time.

Just because they owned slaves though did not mean they were treated equally among slaveowners. As Ellison subtly hints in his letter, white slave owners would avoid interacting with African Americans as much as possible. Ellison provided many whites in the area with what were the best cotton gins available which meant that if they wanted to produce the most cotton, they would have to do business with them. They would often try to avoid paying him though. Despite the discrimination, blacks owning blacks continued all the way up to the Civil War, with many African American slave owners, including Ellison, contributing and supporting the Confederate side. Stories like Ellison’s and other black slave owners showed the economic power of slavery in Southern America in the nineteenth century.

The easiest way to achieve financial and social success was to own slaves and the allure of southern wealth was enough that it convinced a few of slavery’s former victims to switch to the other side.