About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

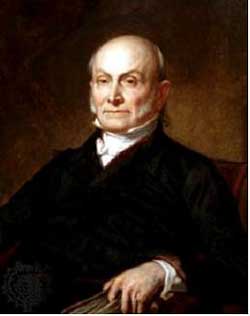

John Quincy Adams, (1767-1848), 6th President of the United States. He was the son of John Adams, 2nd president. Independence and Union were the watchwords of his career; a Union of the United States of North America to grow by the destiny of Providence and nature to become a continental republic of free men stretching from ocean to ocean and from Gulf to Arctic.

“The Second Adams” was the only son of a president to become president; in fact, his parents actually trained him for highest office. His mother told the boy that some day the state would rest upon his shoulder. As he grew up with the new nation, he had during his long lifetime two notable careers, separated by a strange interlude. The first career was as an American diplomat who rose to become secretary of state. The second career was as a member of the House of Representatives and opponent of slavery. The strange interlude was as president of the United States; for four years the state did indeed rest, uneasily, upon his shoulder. Never publicly popular, often reviled by his political enemies, he nevertheless ended his life in the sunshine of national esteem.

Early Life

John Quincy Adams was born in Braintree, Mass., on July 11, 1767. During the first years of the American Revolution, he received his education principally by instruction from his distinguished father and gifted mother, the incomparable Abigail. As a boy of ten he accompanied his father on diplomatic missions to Europe. There he learned French fluently in a private school at Paris; next he studied at the University of Leiden. In 1782-1783 he accompanied Francis Dana, as secretary and interpreter of French (then the language of the Russian court), on a journey through the German states to St. Petersburg, returning to Holland by way of Scandinavia and Hannover.

Adams was already extraordinarily well versed in classical languages, history, and mathematics when he returned to the United States in 1785 to finish his formal education at Harvard (class of 1787). After studying law at Newburyport, Mass., under the tutelage of Theophilus Parsons, he settled down to practice at Boston in 1790.

Diplomatic Career

The young lawyer came particularly to George Washington’s attention because of articles he published in Boston newspapers defending the president’s policy of neutrality against the diplomatic incursions of Citizen Genet, the new French Republic’s minister to the United States. As a result Washington appointed Adams as U.S. minister to the Netherlands, where he served from 1794 to 1797. At The Hague, Adams found himself at the principal listening post of a great cycle of European revolutions and wars, which he continued to report faithfully to his government both from the Netherlands and from his later post as minister to Berlin in 1797-1801. While on a subsidiary mission to England, connected with the exchange of ratification’s of Jay’s Treaty, he married on July 26, 1797, Louisa Catherine Johnson, one of the seven daughters of Joshua Johnson of Maryland, U.S. consul at London.

President John Adams relieved his son of the post at Berlin immediately after Jefferson’s election in 1801. Returning to Boston, John Quincy Adams resumed the practice of law but was soon elected in 1803 as a Federalist to the U.S. Senate. His independent course as a senator dismayed the Federalist leaders of Massachusetts, particularly the Essex Junto. When he voted for Jefferson’s embargo, they in effect recalled him by electing a successor two years ahead of time. Adams was then also serving as Boylston professor of oratory and rhetoric at Harvard (1806-1809). He had once more turned to the law when President Madison appointed him as the first minister of the United States to Russia, where he served from 1809 to 1814.

At the court of Alexander I, Adams again was diplomatic reporter extraordinary of the great events of Europe, including Napoleon’s invasion of Russia and his subsequent retreat and downfall. Meanwhile the War of 1812 had broken out between Britain and the United States. After Alexander’s abortive attempts at mediation, Adams was called to the peace negotiations at Ghent, where he was technically chief of the American mission. He next served as minister of the United States to England from 1815 to 1817.

As a diplomat John Quincy Adams had made very few mistakes, influenced many people, and made many friends for his country, including particularly Czar Alexander I. His vast European experience made him a vigorous supporter of Washington’s policy of isolation from the ordinary vicissitudes and the ordinary combinations and wars of European politics.

Secretary of State

President James Monroe recalled Adams from England to become secretary of state in 1817. He held the office throughout Monroe’s two administrations, until 1825. As secretary, Adams, under Monroe’s direction and responsibility, pursued the policies and guiding principles that he had practiced in Europe. More than any other man he helped to crystallize and perfect the foundations of American foreign policy, including the Monroe Doctrine, which, however, appropriately bears the name of the president who assumed official responsibility for it and proclaimed it to the world.

Adams’ greatest diplomatic achievement as secretary of state was undoubtedly the Transcontinental Treaty with Spain, signed on Feb. 22, 1819 (ratified Feb. 22, 1821). By this treaty Spain acknowledged East Florida and West Florida to be a part of the United States and agreed to a frontier line running from the Gulf of Mexico to the Rocky Mountains and thence along the parallel of 42degrees to the Pacific Ocean. In this negotiation, Adams took skillful advantage of Andrew Jackson’s military incursions into Florida and of Spain’s embarrassment in the revolutions of her American colonies. Over the opposition of Henry Clay, ambitious speaker of the House of Representatives, Adams deferred recognition of the independence of the new states of Spanish America until the Transcontinental Treaty was safely ratified. Immediately afterward President Monroe recognized Colombia, Mexico, Chile, the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, and later Brazil and the Confederation of Central America. Peru remained to be recognized by Adams as Monroe’s successor. The idea of drawing the frontier line through to the other ocean in the Spanish treaty was Adams’ own inspiration. It has been called “the greatest diplomatic victory ever won by a single individual in the history of the United States.”

At the same time Secretary Adams defended the northeastern frontier against proposed British “rectifications” and held the line of 49degrees in the Oregon country. Except for an over contentious wrangle on commercial reciprocity with the British West Indies, his term as secretary of state, in the aftermath of Waterloo, was marked by unvarying successes, including the Treaty of 1824 with Russia. He was perhaps the greatest secretary of state in American history.

Presidency

John Quincy Adams may have been the greatest U.S. secretary of state, but he was not one of the greatest presidents. He was really a minority president, chosen by the House of Representatives in preference to Andrew Jackson and William H. Crawford following the inconclusive one-party Election of 1824. In the popular contest Jackson had received the greatest number of votes both at the polls and in the state Electoral College, but lacked a constitutional majority. Henry Clay, one of the four candidates in 1824, threw his support to Adams in the House in February 1825, after secret conferences between the two, thus electing Adams on the first ballot. The supporters of Jackson and Crawford immediately cried “corrupt bargain”: Clay had put Adams into the White House in order to become his secretary of state and successor. The judgment of historians is that there was an implicit bargain but no corruption.

President Adams believed that liberty had already been won–at least for white people–by the American Revolution and that this liberty was guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States. His policy was to exert national power to make freedom more fruitful for the people. Accordingly he called for strong national policies under executive leadership: the Bank of the United States as an instrument of the national fiscal authority; a national tariff to protect domestic industries; national administration of the public lands for their methodical and controlled disposal and settlement; national protection of the Indian tribes and lands against encroachments by the states; a broad national program of internal physical improvements–highways, canals, and railways; and national direction in the field of education, the development of science, and geographical discoveries. He preferred the word “national” to “federal.” His outlook anticipated by nearly a century the “New Nationalism” of Theodore Roosevelt and (by a strange reversal in Democratic Party policy) of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Adams as president was too far in advance of his times. The loose democracy of the day wanted the least government possible. And the South feared that his program of national power for internal improvements, physical and moral, under a consolidated federal government might pave the way for the abolition of slavery. He had no real party to back him up. The opposition, with Andrew Jackson as its figurehead and “bargain and corruption” as its battle cry, combined to defeat him for reelection in 1828.

Congressman

In November 1830, more than a year and a half after Adams left the White House, the voters of the 12th (Plymouth) District of Massachusetts elected him to Congress. He accepted the office of congressman eagerly, feeling himself not a party man but, as ex-president, a representative of the whole nation. As a member of Congress the elderly Adams displayed the most spectacular phase of his lifelong career of public service. He preached a strong nationalism against the states’ rights and pro-slavery dialectics of John C. Calhoun. Never an outright abolitionist, he considered himself “bonded” by the Constitution and its political compromises to work for universal emancipation, always within the framework of that instrument. Single-handed he frustrated the Southern desire for Texas in 1836-1838. In 1843 he helped defeat President John Tyler’s treaty for the annexation of Texas, only to see that republic annexed to the United States, by joint resolution of Congress in 1845, after the election of James K. Polk over Henry Clay in 1844.

Adams tried in 1839 to introduce resolutions in Congress for constitutional amendments so that no one could be born a slave in the United States after 1845, but the “gag rule” prevented the discussion of anything relating to slavery. “Old Man Eloquent,” as Adams was nicknamed, staunchly defended the right of petition and eventually overthrew the gag in 1844. An abolitionist at heart but not in practice, he tried to postpone the sectional issue over slavery until the North was strong enough and sufficiently united in spirit and determination to preserve the Union and abolish slavery if necessary by martial law.

The Adams Legacy

Personally John Quincy Adams was a man of gruff exterior and coolness of manner–given to ulcerous judgments of his political adversaries, but binding friends to himself with hoops of steel. He was, before Woodrow Wilson, the most illustrious example of the scholar in politics. During all the controversies over slavery, the tariff, Texas, and Mexico, he correctly divined the sentiments of his own constituents. His fellow citizens regularly elected him to Congress from 1830 on, and he died in the House of Representatives on Feb. 23, 1848: “This is the last of earth. I am content.”

Of Adams’ three sons, only one, the youngest, Charles Francis Adams, minister to Britain during Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, survived him. Charles Francis Adams’ four sons, including three famous historians (Charles Francis Adams, Henry Adams, Brooks Adams), carried on the traditions of the Adams family.